Giant Mine Machine Devours Senegal’s Fertile Coast in International Spotlight

Similar to a scene from the sci-fi movie “Dune,” the so-called “world’s largest mining dredge” has been engulfing one plot after another of the productive coastal farmland responsible for growing most of Senegal’s vegetables.

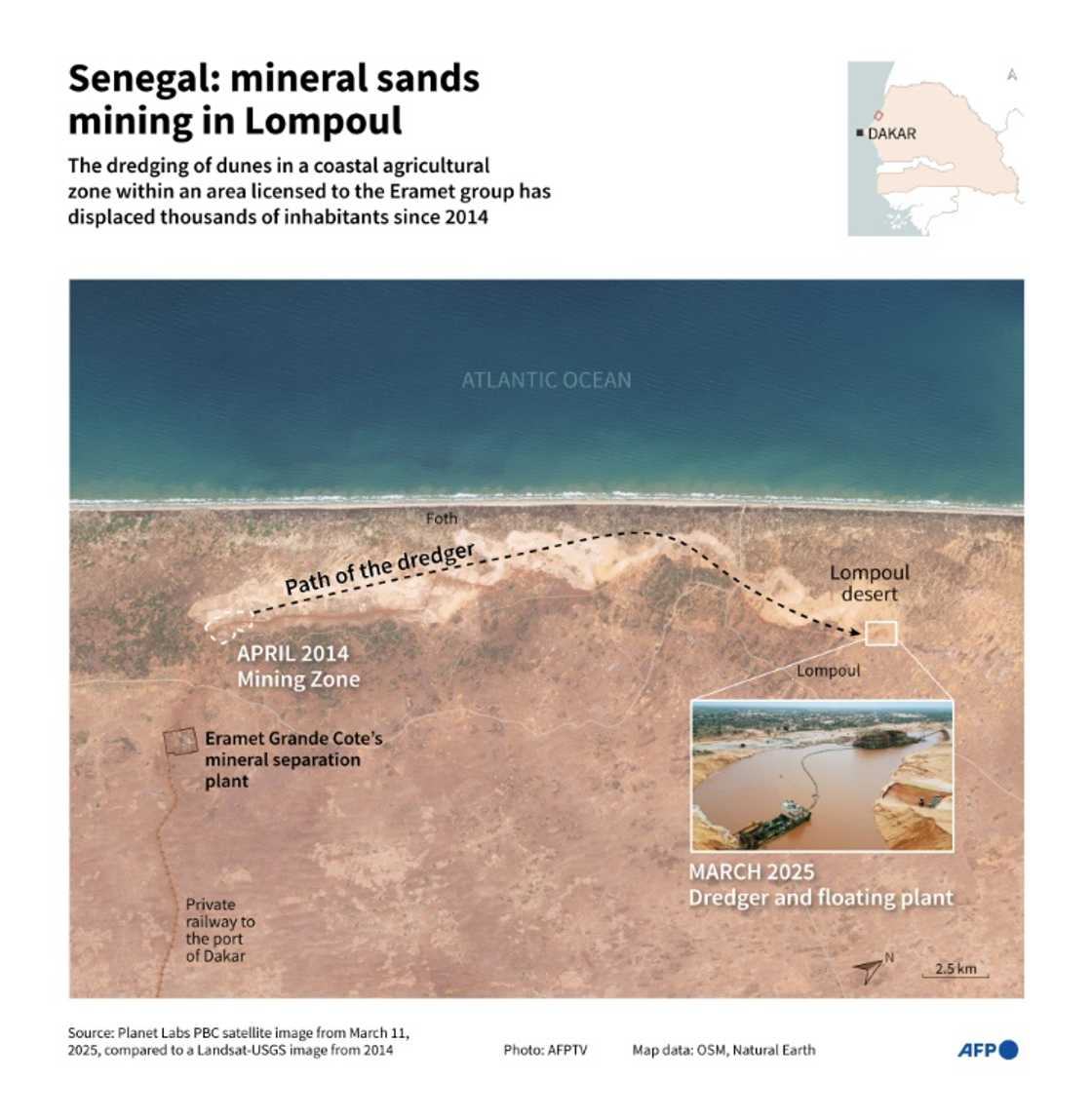

The massive drill has created a rugged 23-kilometer (14-mile) long gash, noticeable even from orbit, caused by extracting zircon, a material utilized in ceramics and construction projects.

In the midst of a thunderous noise, the enormous machinery extracts thousands of tons of mineral sand every hour, advancing across an artificial lake formed by water drawn from deep beneath the earth’s surface.

It is currently sweeping across the dunes of Lompoul — one of the tiniest yet most stunning deserts globally — which attracts many visitors with its never-ending beaches along Senegal’s Atlantic coastline.

Over the last ten years, thousands of farmers along with their families have been forced from their homes to accommodate the massive mobile processing plant operated by Eramet, the French mining company.

It refutes all allegations of misconduct, maintains that its practices are models of excellence, and intends to accelerate its extraction activities.

However, locals blame it for damaging this vibrant yet fragile environment at the western fringe of Africa’s semi-arid Sahel zone.

The initiative has caused “disappointment and disenchantment,” according to Gora Gaye, who serves as the mayor of Diokoul Diawrigne district, which includes Lompoul.

For many years, critics of the mine argued that the villagers’ objections to losing their land were disregarded, as grievances regarding “inadequate” compensation were suppressed by the authorities.

New president speaks out

This situation has shifted, as tourism operators have joined forces with farmers and community leaders to call for a halt in mining activities.

Senegal’s President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has addressed the issue of extractive mining practices, stating that certain local communities do not see benefits from these activities. Last week, he reinforced his stance, calling for increased transparency and monitoring of both social and environmental effects.

Last year, his administration came into office pledging a significant departure from previous policies and to restore Senegal’s autonomy, especially from the dominance of the erstwhile colonial ruler, France.

Eramet, which has 27 percent ownership from France, initiated mining operations in 2014 pursuant to the agreement made a decade prior during the preceding administration. In this setup, the Senegalese government retains a 10 percent stake in the domestic affiliate, EGC, responsible for extracting zircon along with titanium-containing substances like rutile and ilmenite.

The AFP received exclusive permission to observe their activities and visit the dredging equipment as well as the facilities where the mineral sands are processed prior to export. The minerals are transported via the firm’s dedicated railway line, which leads from these processing sites directly through the port located in Senegal’s capital city, Dakar, approximately 150 miles away to the south.

EGC maintained that it operates as a “reliable corporation,” adhering strictly to its accord with the Senegalese authorities and providing compensation to residents at rates fivefold higher than those stipulated nationally, amounting to payouts between 12,190 and 15,240 euros ($16,575) per hectare.

Fertile oases ‘destroyed’

Yet, what do they have remaining afterward? questioned hotelier Sheikh Yves Jacquemain, operator of an environmentally friendly lodge featuring traditional tents in Lompoul. He noted that up until recently, the sole noises heard were those of seagulls and roaming camels.

The mining operation continues ahead; the well-being of individuals after the mine leaves is no longer considered our concern,” he stated for AFP. The thunderous noise from the massive excavator, located just 150 meters (165 yards) away, nearly overwhelmed his voice as it consumed the surroundings.

Out of Lompoul’s seven tourist camps, six have received funds from EGC and subsequently relocated. However, Jacquemain is standing firm, seeking what he considers fair compensation for himself along with his 40 staff members.

Local communities also accuse the mine of destroying and “degrading the soil and the dunes” and threatening their water and food security.

Farmers argue that the reimbursement for the land follows guidelines from the 1970s and fails to compensate for the irreversible loss of income from what were formerly productive fields.

The depressions among the sand dunes served as oases, hosting a unique ecosystem “that previously accounted for about 80 percent of the fresh vegetables consumed in Senegal,” Mayor Gaye stated.

We desire the return of our territory.

Gaye mentioned that the locals were first hopeful regarding the mining activities.

However, what they have received so far are “disrupted commitments, coercion, the devastation of our environment, and the disastrous relocation of communities. The economic progress has regressed,” he further stated.

EGC maintains that it has relocated farmers and their families into four sizable new settlements featuring contemporary amenities.

“In total, 586 homes and community facilities (such as a healthcare center, school, and mosques) have been constructed,” benefiting 3,142 individuals.

However, in the plaza of one of the newer settlements in Foth, Omar Keita and roughly two dozen other family leaders did not hesitate to express their frustration.

“Ideally, we would like to reclaim our land and have our village reconstructed so that we can return to our previous way of life,” said Keita, who is 32 years old, speaking with AFP. “I am appealing to both the president and also to France,” he added.

He mentioned that he wasn’t provided with a new place to live and demonstrated to AFP the conditions where his wife and their three kids have been residing over the last six years—a lone room “borrowed from my elder sibling,” complete with just a mattress on the ground.

However, EGC’s managing director Frederic Zanklan maintained that each household was resettled according to their status at the time of the census, and he stated that it was not their responsibility if those households had increased in size since then.

But Keita said that before he was displaced “I had my fields and my house… We earned our living decently but they reduced that to naught and I have to start again from zero…”

He mentioned, ‘I find myself working in others’ domains here.’

Ibrahima Ba, aged 60, was also furious. He stated to AFP, “We have regressed in every aspect.”

Although I am still a farmer, the yields of today bear little resemblance to those from “my village, where the earth was rich, we had access to freshwater, and encountered no issues.”

He appealed to President Faye and his prime minister for assistance, stating that “a foreign nation is ruining the lives of Senegalese citizens.”

However, EGC’s Zanklan stated that the mining group strictly adhered to the legal requirements and contended that “the project is advantageous for the country… contributing 149 million euros to Senegal’s economy in 2023.”

He mentioned that they had paid “25 million euros in taxes and dividends” on their 215-million-euro revenue.

Approximately 2,000 individuals are employed at the mine and its processing plants, where 97 percent are from Senegal,” Zanklan further noted, adding that almost half of these workers come from local areas.

According to information provided by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, he mentioned that the firm contributed the fourth-largest amount among mining companies to Senegal’s national budget.

The managing director stated that EGC is the “first mining company to restore and return reclaimed land to Senegal,” followed by planting trees on it.

But locals complain that the land is not “returned” to them but to the Senegalese state, which has traditionally allowed farmers to till state land.

“The commitment was made to return the land to us for our continued use, yet they have failed to uphold their end of the bargain,” stated Farmer Ba.

Calls for moratorium

Near the area where AFP observed the rehabilitated land, farmer Serigne Mar Sow indicated the discolored pools in an arid field, stating they demonstrated the “inestimable harm” caused by the mining operations.

The water extracted from 450 meters below ground level for use with the dredging equipment stays near the top of the lake. EGC claims that this provides advantages for farmers growing vegetables.

However, Sow has a different perspective. He says, “The vegetables and bananas that we used to cultivate here have perished due to the floodwater coming from the dredger located 2.5 kilometers away.”

“The soil is now infertile,” he stated.

Encircled by lifeless manioc and banana plants, he asserted that the water had been contaminated with “chemicals.”

About 15 to 20 areas nearby have been left unused due to the water rising — resulting in a significant reduction in arable land for crops.

However, EGC maintains that “no chemicals are employed,” and asserts that the extraction process is “entirely mechanical.”

Gaye, who serves as the mayor of Diokoul Diawrigne, has called upon Senegal to temporarily halt mining activities. He argues that this pause should allow for thorough investigations into the damages incurred and enable a comprehensive assessment of the impacts on both the state and local communities.

He contended that we must not turn a blind eye” to the experiences of others, regardless of “what Senegal receives from this venture.

Zanklan argued that “there is no necessity for a moratorium… If concerns arise, the authorities can conduct inspections at their convenience.”

Indeed, EGC aims to boost the dredger’s capacity by over twenty percent to 8,500 tons per hour starting from 2026, according to him.

Stopping mining operations “would result in 2,000 individuals losing their jobs and halt the economic advantages for Senegal as a nation — such an action would be irresponsible when the country genuinely requires development,” he contended.

Meanwhile, the dredger keeps consuming the sand dunes of Lompoul, which stands as Africa’s tiniest yet most picturesque desert.

Share this content:

Post Comment